What’s great about history is that events are named after something logical. For example, the 1859 Battle of Solferino takes its name from where the conflict actually took place – Solferino in Italy. It was one of the largest battles since the 1813 Battle of Leipzig, which, guess what, takes its name from the place of the battle – Leipzig. In the former there were estimated to have been 300’000 combined soldiers involved, and as you can imagine a great deal of blood was shed, with many killed and more wounded.

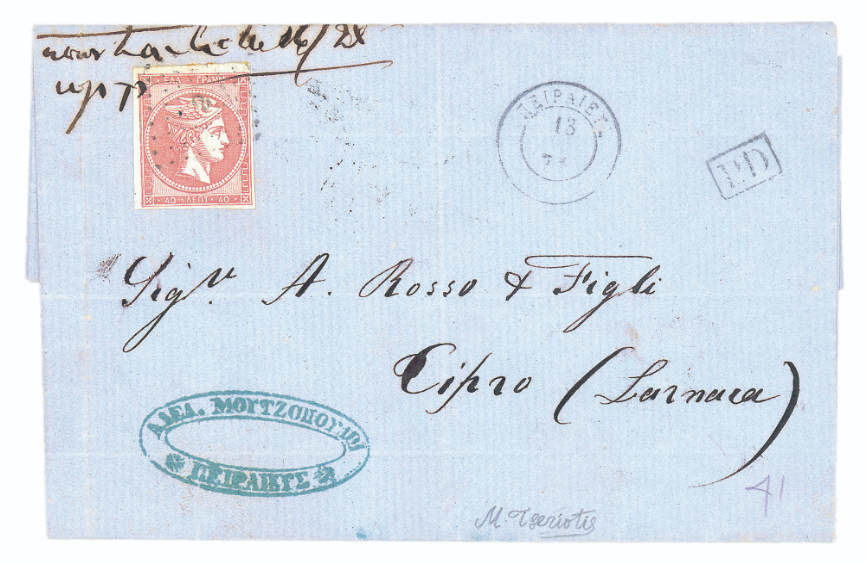

However, two positive things came out of the Solferino battle, one was the International Red Cross, which found its inspiration in a Swiss humanitarian, from Geneva, a chap called Henri Dunant (1828 to 1910) who visited the battlefield in the aftermath and was so moved by the suffering and neglect of the wounded soldiers he wrote a book called ‘A Memory of Solferino’ which is recognised as the root for the International Committee of the Red Cross in 1863. The other positive, albeit oddly indirectly related, which subsequently came out of the battle, is the rare set of stamps known as ‘The Solferinos’. Our featured item is the famous ‘Solferino Cover’, which is the most valuable item in Greek philately, being the only full cover and sold for 646’250 CHF in 2002, at a David Feldman SA auction. But unlike historical events, it doesn’t take its name from the place it was sent from or going, because it originates from Piraeus, a port town near Athens, and went to Larnaca in Cyprus. It actually takes its name from the stamp’s colour, which ‘apparently’ relates to the Battle of Solferino.

It’s an macabre one, but according to philatelic history, the 1870 40 Lepta Lilac-rose stamps, of which there are only 13 recorded, are so called because they are the same shade as the blood stained uniforms of the soldiers from the Solferino battlefield. Given there was an interval of over a decade between the two it’s remarkable that such a connection would be made and more so given this isn’t an Italian stamp, let alone a French one or Austrian, the three belligerents in the bloody affair in Solferino. So, the origins of this philatelic name, given to an ancestral line of stamps of Greek extraction, with no blood relation with the battle in question and aren’t obviously blood-red in appearance, strikes as a bit of a bold if not gory choice.

Today, it certainly seems a tenuous connection, however, perhaps the reality is that when baptised, so to speak, in the blood of the Solferino battle, the memory of that conflict was more vivid than it is right now and Henri Dunant’s book, which contains the author’s first hand observations from the stained Solferino countryside, were still fresh in the forefronts of hearts and minds of the international community, and clearly the philatelic one’s too. And whilst today we may have less of an awareness of what these types of conflicts look-like, the price of them was always paid in the precious blood of soldiers. So, it’s perhaps more adpt than first considered that a stamp being of such a precious colour, which is rarely seen, should bear the name of a poignantly visual memory. Whilst history tends to be objective in its naming of events, philately at times can be esoteric when identifying material.

This cover is actually the philosophical embodiment of a particular bloodline of stamps which finds it’s genealogical heritage not in origins or destination, but in its evocative appearance to those who beheld it for the first time. The colour being its defining feature because it should have been either mauve or bistre. Whatever the reason that title has clung to the life of these stamps ever since, not unlike the name of the battle itself, only without a hint of conflict from anywhere, let alone Solferino.